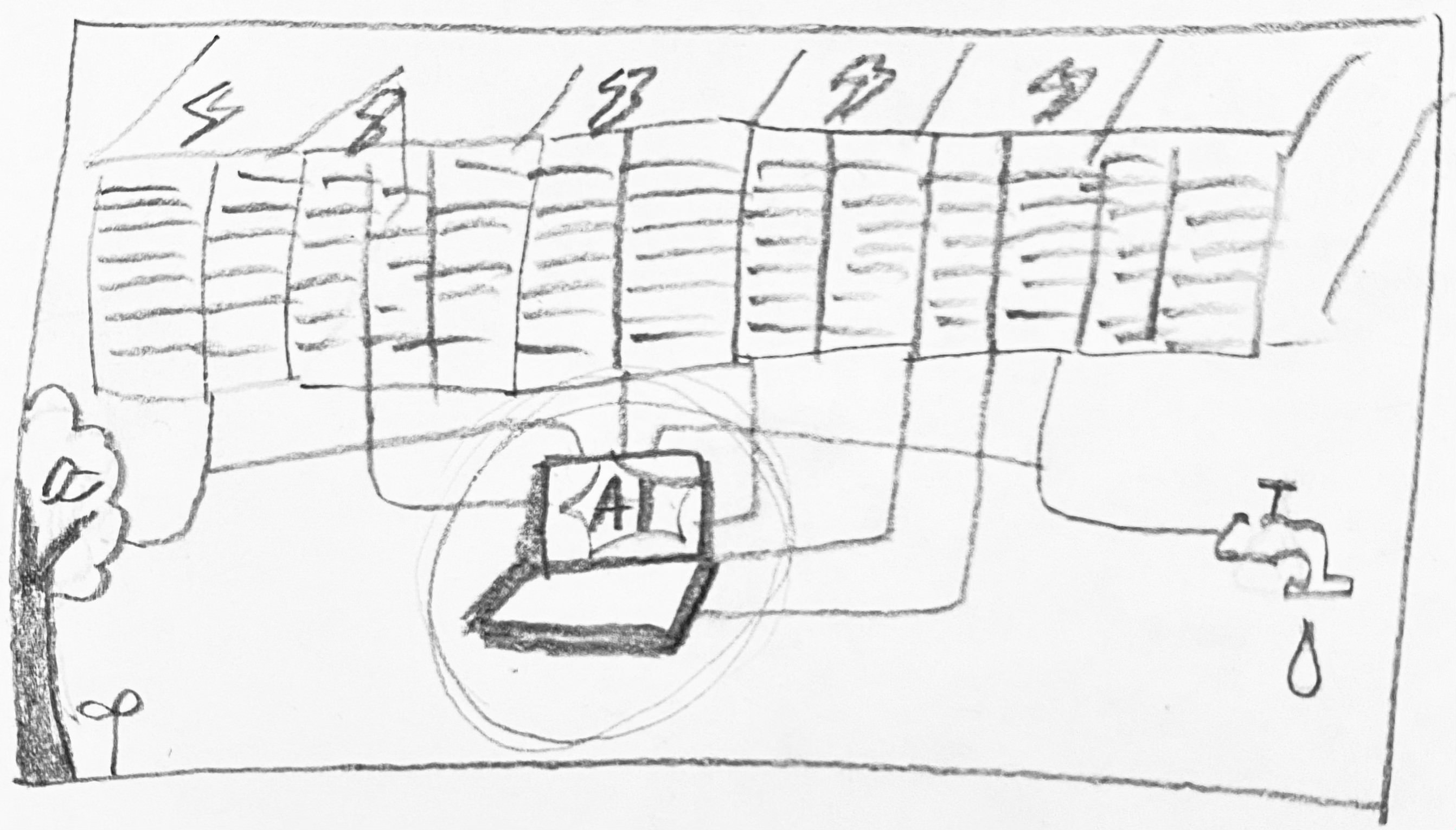

Drawing of datacenters connected to water tap, trees and a computer labeled "AI". Image: Hannah Yi

AI’s rapid growth is not only a story of innovation–it is also a story of sustainability. Recent reporting shows that nearly two thirds of new data centers since 2022 are being built in water scare regions, elevating risks that extend beyond carbon to water scarcity and community impact.¹

In this context, Google published a technical paper estimating the footprint of its Gemini App prompts: 0.24 Wh of energy, 0.03 gCO₂e, and 0.26 mL of water per prompt. That is roughly equivalent to igniting a LED lightbulb for 90 seconds, driving a car for 0.25 meters, and 5 drops of water.²

These results are meaningful, but scope and method matter. The study reports median serving only metrics, excluding networking, end user devices, and training, which are essential to AI’s full lifecycle footprint. The findings also reflect Google’s optimized TPU hardware, batching strategies, and efficient data centers–conditions unlikely to hold for smaller providers or academic labs. On carbon, Google reports 0.03 gCO₂e per prompt using market based (MB) accounting, which credits renewable energy purchases. This systematically lowers emissions compared to location based (LB) methods, which track the actual carbon intensity of the local grid. The Green Mirage study shows that MB and LB approaches can diverge by up to 55.1%, and in some cases MB accounting can mask increases in emissions.³ While MB is a GHG Protocol accepted standard, making Google’s choice legitimate, it also complicates cross comparisons with studies that use LB metrics.

The dataset is also specific to Gemini Apps and not representative of AI workloads more broadly. As a movie director intentionally frames each shot, corporations frame information strategically. Still, Google deserves recognition for publishing production grade measurements in a field where transparency is rare. As one of the first real world benchmarks, the study provides a baseline for debate–even if its methodological choices limit universality.

Conclusion

Google’s analysis illustrates real efficiency gains and sets a benchmark for transparency. Yet its scope, median framing, and reliance on MB accounting mean the reported footprint is best understood as a lower bound in an optimized setting, not a definitive measure of AI’s environmental cost. Placed alongside evidence that many new data centers are concentrated in water scarce areas and AI’s power demand is accelerating globally, the larger picture comes into focus: the sustainability challenge is systemic, not provider specific. Governing this growth will require standardized accounting, broader lifecycle boundaries, and siting decisions aligned with water and energy constraints to ensure that efficiency gains translate into verifiable reductions in both carbon and water risk as AI scales.

Sources

¹Nicoletti, Leonardo, et al. “How AI Demand Is Draining Local Water Supplies.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 8 May 2025, www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2025-ai-impacts-data-centers-water-data/.

²Elsworth, Cooper et al. “Measuring the Environmental Impact of Delivering AI at Google Scale.” ArXiv.org, 2025, arxiv.org/abs/2508.15734. Accessed 7 Sept. 2025.

³Maji, Diptyaroop, et al. “The Green Mirage: Impact of Location- and Market-Based Carbon Intensity Estimation on Carbon Optimization Efficacy.” ArXiv (Cornell University), Cornell University, June 2024, https://doi.org/10.1145/3632775.3639587.